Tumors on dogs’ legs are common – and while they can be benign, unfortunately malignant tumors are also common, so it’s worth getting them checked by a veterinarian. In the meantime, let’s find out more about what tumors you might find on your dog’s legs.

Tumors often found on dogs’ legs

1. Mast cell tumors

Mast cell tumors account for 16 to 21% of skin tumors in dogs. They’re malignant (cancerous), although some are more aggressive than others. Their appearance can be very variable, but they frequently grow quickly as a hairless, often inflamed looking mass; ulceration is also common as they become larger. One unusual trait of mast cell tumors is that they can swell as the mast cells release inflammatory molecules, resulting in a tumor that fluctuates in size.

While some mast cell tumors remain small, others can become extremely large. However, even small mast cell tumors can spread to other sites including the lymph nodes, liver and spleen – so early diagnosis and treatment is essential. Treatment is usually surgical, with chemotherapy if needed. The prognosis can be good for low grade tumors that haven’t spread – but for more aggressive tumors, it’s unfortunately poorer. View more pictures of mast cell tumors.

2. Papillomas (warts)

Caused by a papilloma virus, warts are common in young dogs. They’re often seen on legs and paws, growing as small (< 3cm), hairless, cauliflower-like growths with an irregular, bumpy surface. They can be pink, tan or pigmented. These growths usually resolve over several weeks to months – if your dog is older, they last longer, or there are signs of irritation it’s worth getting them checked by your vet. Pictured below is an example wart on a dog’s leg. View more pictures of warts.

3. Sebaceous adenomas (‘old dog warts’)

These benign tumors develop from sebaceous glands in the skin and are frequently confused with true warts (papillomas). Adenomas are much more common than papillomas in older dogs, and don’t resolve with time like true warts – however, their appearance can be very similar, with adenomas typically developing as hairless, well-defined, cauliflower-like masses of variable color. Just like warts, these tumors don’t typically cause irritation or inflammation, but if traumatized may become sore. They don’t typically need treatment, but if they’re becoming traumatized or otherwise causing a problem, surgery is usually curative. Pictured below are adenomas on a dog’s leg. Learn more about sebaceous adenomas.

4. Soft tissue sarcoma

Soft tissue sarcomas consist of a group of tumors that arise from connective tissues. They’re cancerous and typically very locally invasive, making treatment challenging. These tumors usually feel firm and fibrous, often with a slightly bumpy, irregular shape. They develop within or under the skin, and the skin surface may or may not be affected; larger tumors may develop ulceration or hair loss.

Early diagnosis and treatment of these tumors on the legs is particularly critical – treatment relies on surgical removal with wide margins of up to 3cm, meaning even a small tumor requires extensive surgery. On the legs, it can be difficult to remove sufficient margins – so the prognosis is much better if the tumor is small.

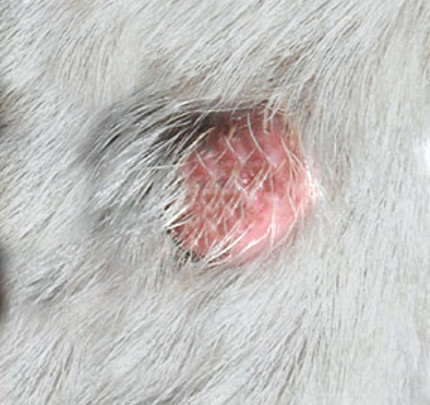

5. Histiocytomas

These benign tumors are usually seen in young dogs, although they can occur at any age. They usually grow on the head and legs, appearing as solitary, raised, red or pink hairless nodules. Histiocytomas are unusual in that they usually develop rapidly and appear inflamed – characteristics which typically suggest a malignant tumor. However, histiocytomas should resolve spontaneously within a few months.

If you suspect a histiocytoma, it’s worth getting it checked by your vet – especially if your dog is over 3 years old, as other growths like mast cell tumors can appear very similar.

6. Melanoma

Melanomas develop from melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells of the skin. Two thirds of melanomas in the skin are benign – although those on the toes are more likely to be malignant. These tumors usually develop as smooth, well defined, dark, hairless growths – although some grow without any pigment. Malignant melanomas are more likely to develop ulceration and inflammation.

Treatment is usually surgical, and success depends on how aggressive the tumor is – in the case of benign skin melanomas, treatment may or may not be required, whereas for aggressive melanomas on the toes amputation of the affected toe may be necessary.

What to do if you find a tumor on your dog’s leg

Finding a lump you think is a tumor can come as a shock, so it’s normal to be worried and need some time to process it – and for tumors, a couple of days is unlikely to make a significant difference. However, for many of these tumors early diagnosis is critical, so it’s best to book in to see your vet as soon as you can.

In the meantime, if you notice any ulceration some gentle saltwater bathing may help. If your dog is licking or chewing at the area, a buster collar may also help to prevent self-trauma and infection until you can see a vet.

Veterinarian diagnosis

For most of these tumors, your vet will recommend a fine needle aspirate to get a definitive diagnosis. This consists of using a small needle (like those used for a vaccine) to get a small sample of cells to assess under the microscope – and it doesn’t require any sedation for most dogs. For many tumors, this is sufficient, but for some (like soft tissue sarcomas), it may not provide a good enough sample, so a biopsy may be required. This requires sedation or anesthesia. Depending on the lump, your vet may recommend fully removing it and sending it away for analysis.

For some of these lumps, however, your vet may recommend a ‘wait and see’ approach – in young dogs, for example, histiocytomas and warts are common and malignant tumors are very unlikely.

References

Dobson, J. M., & X., L. B. D. (2011). BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Oncology. British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Kim, S., & Matsuyama, A. (2022). Canine mast cell tumors: When to worry about aggressive behavior pre-surgically. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne, 63(12), 1261–1263.

Disclaimer: This website's content is not a substitute for veterinary care. Always consult with your veterinarian for healthcare decisions. Read More.

Be the first to comment